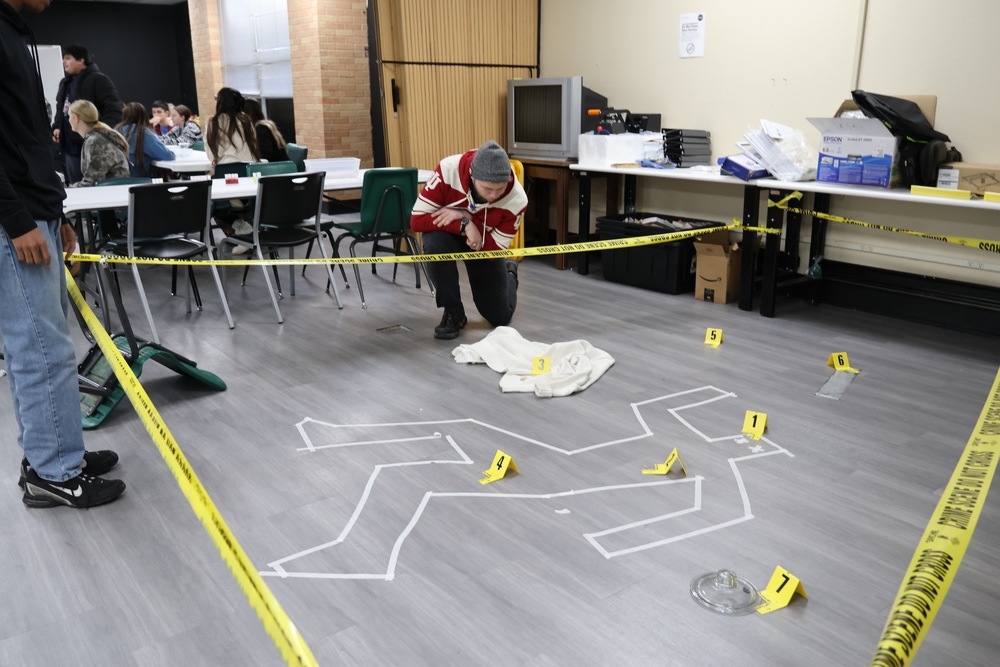

Someone “murdered” the mayor in a back room of the MacArthur High School library and the MHS forensics class was called in to solve the “crime”.

Yellow crime scene tape marked where the “murder” took place, with masking tape outlining where a body was found. Yellow evidence markers identified where blood, a sweater, tire tracks and broken glass also were found. MHS students were busy studying the crime scene and processing the evidence.

MacArthur High science teacher Heather Young said the exercise, called “The Case of the Murdered Mayor”, was part of the final test for students in her forensics class. Students spent the fall semester learning about fingerprinting, comparing blood samples and examining hair samples. Their final project was to process a “crime scene” and determine which of the five suspects may have murdered the mayor at a remote cabin in the woods.

Students were divided into teams and rotated through stations examining the evidence, including fingerprints, hair fibers, blood typing and tire tracks.

And maggots.

Each team was given envelopes containing evidence and a list of five suspects. After students processed the evidence, they were to use the context of the clues to solve the murder by submitting a written report to the fictional district attorney, who would decide whether or not to arrest a suspect and press charges.

Eyan Howard, who was examining slides of hair follicles, said he took the class because it is hands-on and he likes the mystery of it. He said he gets to use slides for the microscope, get fingerprints and use clues to figure out a motive.

He also is learning about teamwork. Team members assigned each other tasks to perform as they tried to figure out who murdered the mayor.

“It’s valuable,” he said about teamwork. “In the real world, you work with people you haven’t worked with before. It helps with people skills. If you don’t understand something, you have other people you can go to.”

He said processing the crime scene allowed students to put the skills they had learned in class to use, adding that fingerprinting was the easiest one to do.

Howard said the class fits into his career plans.

“I have a lot of ideas,” said Howard, who is considering becoming a detective or police officer.

“That has always been cool to me,” he said of those occupations. “I met all those people (fellow students) this year and they may want to do the same thing as me. Being able to do things they do is like a brand new door. This is nothing like on TV. This is a great step.”

Nathan Higuera was part of the team analyzing synthetic blood samples and synthetic serum to determine the blood type on items found at the crime scene.

“If we find a match of blood on the items, we can put them at the scene of the crime,” he said. “We can find out who was bleeding out. If we can tie it to one of the suspects, we will have a stronger case.”

But about those maggots.

Jessica DeVries had one of the more unpleasant tasks of crime scene investigation — examining maggots.

“We had to measure them because they are curved,” she said. “We had to estimate how long they would be if they were straightened out. We put them in the microscope and looked at them. The size is important. You can tell how long the body has been there. The longer it has been there, the bigger it (the maggot) gets.”

DeVries said she took the class because “it seemed like a fun subject. This is just a fun class for me to take.”

Young said processing the crime scene was something students had been building toward all semester.

“You show them how it all applies. They see all the stuff they have learned applied to the real world,” she said.

During the spring semester, students will continue to study evidence and will discuss courtroom procedures. They also may work with a history professor to do criminal profiling.

“Who knows, we might solve a real crime,” Young said.

But who killed the mayor?

Young said the students may never know, although she knows who is guilty. The students’ job is to analyze the evidence and write their report based on where the evidence leads them, she said.

“In the real world, the detectives never know,” she said.